The Strange Journey of Activision

When you hear the name Activision, you probably think Call of Duty, all manner of misconduct allegations, and probably their absurdly overpaid CEO Bobby Kotick. While their properties do make them a ton of money, Activision isn’t exactly a well-loved developer these days, especially for old folks like me.

A Long Time Ago...

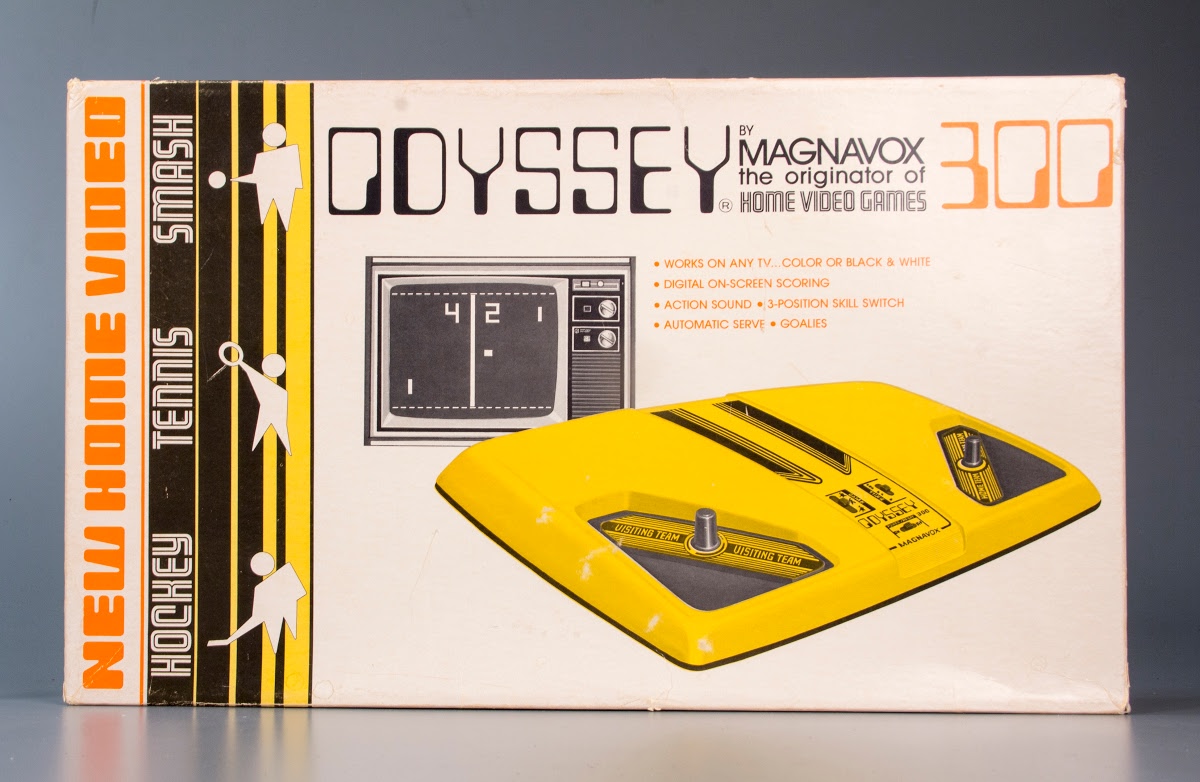

Back in the old days before Activision existed, 3rd party game publishers didn’t exist either. It may be hard to wrap your head around an entire game industry where console makers were the only ones to publish titles for their machines, but before the Atari 2600 popularized the concept, a console with interchangeable games was all but unheard of. Console manufacturers by and large would just release a system with some built-in games, and that was it.

Image: The Strong Museum of Play

After the 2600 hit the scene though, the idea of systems with interchangeable cartridges became the norm, and the 2600 in particular started building up an actual game library.

The trouble was, Atari wasn’t exactly great about giving their game developers actual credit. Where movies and TV shows always rolled credits to let you know who made them, video games came from Atari, not from people. Some folks spoke out about it, and in 1979 David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead left Atari to form what soon became Activision, a company built on the idea of treating game designers as artists instead of tools.

The games that came out of Activision those next few years were among the best around. Sure, they weren’t all all-time classics, but some are still considered to be among the most influential games ever made.

From 1980 through early 1983, Activision was firing on all cylinders. The games they produced for the Atari 2600 were head and shoulders above most of everything else out there. Not only that, their company’s formation opened the floodgates for tons of other 3rd party developers of varying quality.

By the end of 1981, Activision had released a number of hits including Dragster, Kaboom!, and Laser Blast, and things only got better the following year with true legends like Megamania, River Raid, and of course, Pitfall.

The Crash

That train kept on rolling through 1983 when the American video game console market famously crashed and burned. Fortunately for Activision, there were now other avenues to pursue in terms of video game development, particularly the world of home PCs. Many of their greatest hits wound up being ported to platforms like the MSX, Commodore 64, and Atari 8-bit home computer systems, but even though they still had some absolutely killer titles on the way for the Atari 2600 in the form of the truly excellent Beamrider, H.E.R.O., and Pitfall II, the world of video games had changed, and Activision had to find a way to change with it.

By the time Nintendo had revitalized the home console market with their Nintendo Entertainment System, Activision hadn’t put out an original hit in quite some time. They eventually did get around to publishing some titles on the NES, but they were largely pretty awful. Think Ghostbusters, The Three Stooges, and the absolutely dreadful Super Pitfall. A company who once stood as the ultimate bastion of quality in the world of video games had dropped the ball hard, but they did manage to outlive other brands like Imagic, Data Age, and Apollo, while other companies like Mattel, CBS, and 20th Century Fox lived on, but abandoned their stakes in video games.

Things during the 8-bit era were pretty rocky for Activision, but they got better the following generation. They published some genuine hits for the consoles of the era like Pitfall: The Mayan Adventure and various Mechwarrior titles. They weren’t riding high or anything, but they were still around, and doing more or less okay. However, this was after the company had been acquired by one Bobby Kotick for the paltry sum of $500,000. Hilarious to think about Activision being worth only that much these days, right?

Skating to Victory

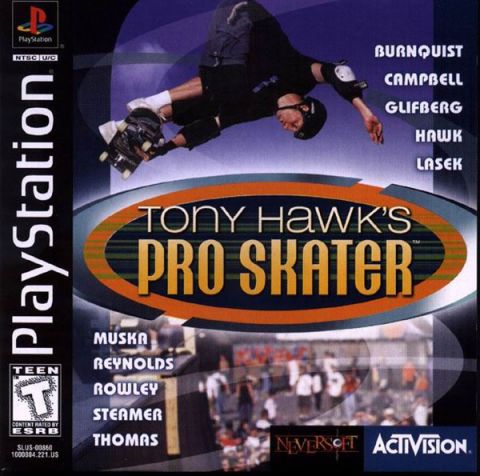

Things remained decent for Activision throughout the remainder of the 90s, with several moderate hits like Tenchu: Stealth Assassins under their belt, but their name didn’t really ring with gamers like Capcom or Konami did. That is, until they released a little game called Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. This game was a massive success, and it put the Activision name back on the map in the biggest way since the Atari 2600 days.

What followed was a string of success stories, and an increasing level of greed. Over the next decade, Activision would churn out a handful of other massive success stories like Guitar Hero and Call of Duty, all of which became annualized until any sense of worth they had was drilled into the ground, with the exception of Call of Duty which has somehow survived the annual onslaught. They merged with Blizzard and gained access to brands like Warcraft and Starcraft, and they acquired the rights to Universal properties like Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon, the latter of which they spun off into the massively successful Skylanders brand, which they also annualized and promptly ran into the ground.

This practice of pumping out sequel after sequel for every successful property they owned became a bit of an industry norm. It was popularized by EA in the sports game arena for decades, but sports titles had a built-in excuse with roster updates and such. These games had no business syncing out year after year other than an insatiable need to make not just more money, but as much money as humanly possible no matter the cost.

Sacrifice of Soul

And that cost was high indeed. Sure, the people at the top in the Activision Blizzard machine are sleeping on gigantic piles of cash, but the Tony Hawk franchise crumbled under the weight of having to try to stay fresh year after year. Guitar Hero had gimmick after gimmick thrown at it in a series of futile bids to stay relevant. Even the moderate success of Crash Bandicoot 4 wasn’t enough to stave off the immeasurable greed of Activision, making Toys for Bob dedicate their time to Call of Duty support instead of continuing to rebuild the Crash brand.

So while money was being made, it came at the cost of creativity. If an Activision game didn’t churn out enough success to become an annual money making machine, those resources were redirected to the projects that would. Loot boxes, live services, every negative buzzword the video game industry could muster got crammed into as many Activision games as possible, and it was profitable, but gross.

Stack that up with the ongoing allegations of terrible working conditions, and now the acquisition by Microsoft, and Activision has become everything the company was founded against. They struck out on their own out of a desire for game creators to be treated with respect and autonomy. They may share the same logo, but they are in no way the same company they once were, and they don’t deserve any of the respect that their legacy content should award them.

Things could get better now that they’re with Microsoft. They’re hardly an angelic corporation, but if there was any chance of a company like Activision becoming something better than the snake pit it is now, it would only have happened with a buyout like this. Corporate consolidation is a scary thing, but in this case, it may actually be better than the alternative. I guess we’ll see.

Now get me Barnstorming 2022!