Mario Bros. Retrospective Part 3 - The Sky is the Limit

Welcome to Part 3 of our Mario Bros. retrospective! In this episode, we take a look at Mario's first proper portable adventure, chronicle his journey to cartoons, comics, and movie theaters, and celebrate one of the most monumental video game releases of all time. In this series, we aim to tell the story of the Mario Bros. series as it unfolded for North American audiences. Once again, this episode delves a bit more deeply into the Japanese side of things because it's impossible to understand the full scope of what was going on with the Mario franchise without looking at what was happening overseas. But back to the point, we are not only looking at the games themselves, but the historical context surrounding them, and what it was like being a fan as these games were being released. 00:00 - Intro 00:15 - Cause for Concern 03:10 - Super Mario Bros. (Game Watch) 05:37 - Super Mario Bros. 3 (PlayChoice-10) 07:04 - Super Mario Land 11:27 - The Super Mario Bros. Super Show 14:31 - The Wizard 17:09 - Super Mario Bros. 3 23:09 - The Nintendo Comics System 23:58 - Super Mario Bros. 3 (Game Watch) 25:05 - Series Evolution Want to learn more about Mario Bros.? Please watch the fantastic Video Works series by Jeremy Parish. https://youtu.be/cdUDvoGFp8s?si=8tZLecvzwVAtWLIJ More invaluable sources that this project wouldn't have been possible without: The Super Mario Wiki: https://www.mariowiki.com/ The Gaming Historian: https://thegaminghistorian.com/ Leonard Herman: http://www.rolentapress.com/ Supper Mario Broth: https://www.suppermariobroth.com/ Watch more Stone Age Gamer Archeology: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLoWJAVdwC7Z_CCqXEIJTcDQhVoxTcmPU7

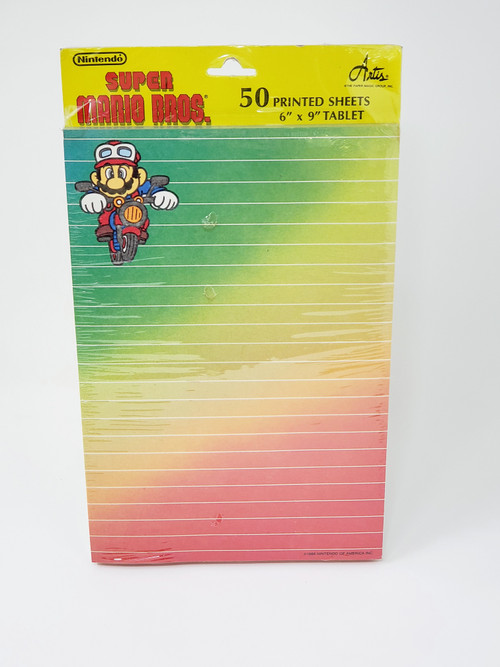

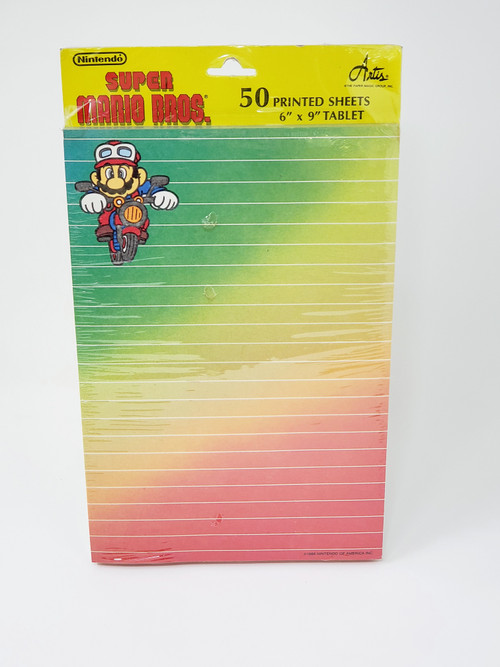

Vintage Super Mario Bros. Notepad (Mario on Bike)

$19.99

Super Mario Bros. "Mario on Bike" Notepad

Vintage (from 1989)

Factory Sealed … read more

Vintage Super Mario Bros. Notepad (Mario on Bike)

$19.99

Super Mario Bros. "Mario on Bike" Notepad Vintage (from 1989) Factory Sealed … read more

Transcript of the video

By late 1988, it seemed like things for Nintendo couldn’t have been going better, especially in the world of Mario. The original Super Mario Bros. was now being bundled in with new NES consoles in a combo cartridge that also included Duck Hunt, while Super Mario Bros. 2 was quickly on its way to becoming another runaway success. But behind the scenes, there were a number of factors that, while largely unnoticed by the public, were cause for concern. 1988’s chip shortage led to some significant game delays, as well as considerable difficulties satisfying consumer demand for their hottest titles. Then there was the Famicom Disk System, which Nintendo had dedicated the bulk of their development resources to, but was now rendered effectively useless thanks to new chip technology that made cartridges more powerful than ever.

As a result, throughout the course of 1988, Nintendo of America only published three internally developed titles for the NES, and 1989 wasn’t shaping up to be much better. Thankfully, they had a robust lineup of 3rd party games to fall back on, even going so far as to publish a number of them themselves.

But back in Japan, Nintendo had just released the latest Mario game, which had quickly become a nationwide phenomenon. The next natural step would normally be to bring it stateside, but between not wanting to cannibalize sales from the recently released Super Mario Bros. 2 and the chip shortage ensuring that creating enough stock for a proper launch would be impossible, some tough decisions would need to be made. Mario’s new adventure was going to have to wait. But even in the age before the internet, there would be no keeping a game that big a secret for long. And its journey to the West would be anything but conventional.

As the home video game market continued to evolve, the arcade business was forced to follow suit. But as other companies continued to push more technically impressive releases that couldn’t be properly replicated on home consoles, Nintendo once again took a different approach. Like their Vs. system, their new line of Playchoice cabinets, the Playchoice 10, would also effectively contain NES hardware. The machines wouldn’t be as visually impressive as other games on the market, but they would also be much easier to update with new titles on a regular basis. In issue 4 of Nintendo Power, a full page was dedicated to promoting the Playchoice system by explaining how it was basically a video game jukebox, with a rotating selection of ten games to choose from.

But far more interesting was what came at the very end of the article. Without any fanfare or buildup, or even information about what it was, Nintendo Power casually announced the existence of Super Mario Bros. 3.

Naturally, for the vast majority of readers who had no idea the game already existed in Japan, there were far more questions than answers, but one thing was certain. Mario’s world was about to get much bigger, but not before getting much smaller.

In early 1989, Nelsonic Industries released the Super Mario Bros. Game Watch. Similar to the Super Mario Bros. Game & Watch by Nintendo, this was an LCD game designed to recreate the Mairo gaming experience on the go, only instead of just being a dedicated handheld, it was also a functioning wrist watch. Nelsonic didn’t try to replicate the NES game’s scrolling stages though, instead opting for a single-screen approach that was more common among LCD games of the time.

According to the instruction manual, Mario’s sweetheart, the Princess, had been kidnapped by a witch, not Bowser. And in fact, the King of the Koopa himself has been reduced to mere henchmen status, here referred to as the Fire Breathing Koopa Dragon.

It was the player's goal to guide Mario through a simple obstacle course to make it to the top of the screen where the Koopa Dragon awaited. In order to accomplish this, Mario needed to grab either a flower or a star on the way to the top of the screen. Once doing so, he could use a special platform that only appeared after obtaining a powerup to cross over the dragon’s head and save the day.

It was an incredibly simple game with a very frustrating control scheme, but the novelty of having something that even remotely resembled Super Mario Bros. on a wristwatch was an enticing proposition. Beyond novelty though, there was no denying that the gameplay on display was a far cry from the industry-defining classic it derived its namesake from. Nintendo fans wanted more, and in time more is exactly what they would get.

Nintendo Power continued to casually acknowledge the existence of Super Mario Bros. 3 while avoiding any details that would give away anything more than its name. That is until the very last page of issue 6, where a small blurb explained that in the game Mario would be able to fly using a raccoon tail as a propeller, and promised to explain more about what that meant in future issues. But that wasn’t the only Mario news they had to offer that month. Tucked away at the bottom of a page detailing upcoming new hardware was a paragraph about a device called Game Boy. Again, very little information was given, aside from a vague promise of it effectively putting an NES in your pocket, but they did list a small number of games that fans could expect to play on it, including something called Super Mario Land.

All eyes would continue to be on Nintendo Power in the coming months to learn as much as possible about Mario’s next adventures, but in arcades, a select few would be able to do more than just read about it. They’d be able to play it.

On July 15th, 1989, Nintendo quietly added Super Mario Bros. 3 to their Playchoice 10 machines, giving arcade goers an exclusive early preview of the highly anticipated game on hardware that was uniquely ill-suited for it.

The Playchoice-10 line had only been at best a moderate success. The cabinets that did manage to get Mario 3 quickly became more popular than ever, but the reality of the situation was that there simply weren’t all that many Playchoice 10s to be found, meaning that the number of people in the game’s target demographic who would even know this arcade preview existed was decidedly miniscule. Not only that, but the Playchoice-10’s gameplay was based on a timer. Whenever you put a quarter in the machine, you weren’t buying lives or continues, you were buying time. If you got a Game Over, you could restart as often as you wanted, as long as you had the cash to cover it. So for a game like Super Mario Bros. 3, a full playthrough for even a skilled player would have easily cost well over $30, and taken nearly 3 hours to complete, far longer than most were likely to spend on a single machine.

Super Mario Bros. 3 on Playchoice-10 was an odd move for Nintendo. They had unceremoniously dropped one of their most important releases in a place that all but guaranteed the vast majority of the public would never find it, but this strange decision didn’t ultimately matter. Because Nintendo was about to launch one of the most successful video game platforms of all time.

Following the success of their NES and Game & Watch lines, Nintendo set out to create a brand new handheld system that would combine the best of both of their previous efforts. The result was the Game Boy.

The hardware would utilize a monochrome dot-matrix display and interchangeable cartridges capable of playing complex games that were well beyond the limitations of a Game & Watch. Technologically, it would still pale in comparison to upcoming competing efforts from the likes of Atari and Sega, but Nintendo had little interest in prioritizing cutting edge electronics. Instead, they focused their attention on making sure that the system was cost effective, supported a long battery life, and launched with a full slate of its biggest selling point of all, its games.

The bulk of the Game Boy’s marketing centered around promoting Tetris, an easy to learn, yet difficult to master addictive puzzle game that would serve as the system’s pack-in title. But, Tetris was just one part of the launch lineup, and for as exciting as this new puzzle craze was, another game was garnering just as much attention from Nintendo’s core audience, Mario’s first fully realized portable adventure.

Super Mario Land released in July 1989 for the Game Boy, and brought 2d side scrolling Mario madness to pockets, backpacks, and car trips everywhere. Visually, it was an enormous step backwards from Super Mario Bros. 2, but even with the Game Boy’s incredibly low resolution screen, the game managed to pull off a look that was undeniably Mario, albeit with a decidedly offbeat flair.

The primary Super Mario Bros. team, lead by Shigeru Miyamoto, was busy working on other projects, so development duties fell to a different team entirely. As a result, Super Mario Land featured a noticeably different feel from its home console brethren, including the game’ story which now saw Mario facing off not against magic or dreams, but an alien invasion.

In a once-peaceful world called Sarasaland, an extraterrestrial menace named Tatanga had invaded. He hypnotized the people of its four kingdoms to do his bidding, and made plans to marry Princess Daisy, who made her series debut here. Mario, this time without his brother since this was a strictly single player affair, had to travel the land to rescue Daisy, fend off the invading alien forces, and battle hypnotized Sarasaland denizens along the way.

Returning powerups like the Star that made Mario invincible and the Super Mushroom that turned him into Super Mario helped keep things familiar, while some fascinating new abilities were on hand to keep things fresh. Replacing the Fire Flower was a different plant simply referred to as the Flower, which granted Mario the Superball ability. Where fireballs would bounce along the ground, Superballs would bounce off walls and fly through the air diagonally for a limited time. In addition to defeating enemies, they could even be used to collect coins. Mario could also climb aboard a pair of new vehicles for auto scrolling shooter stages. The Marine Pop was a submarine, while the Sky Pop was an airplane. Both controlled identically, allowing Mario free movement around the stage and the ability to shoot enemies and obstacles.

The four kingdoms of Sarasaland were unlike anywhere Mario had traveled before, featuring environments composed of fantastical interpretations of real-life locales like Egypt, Easter Island, and China. The visuals were more simplistic than those found in Mario’s home console counterparts, but the game was still able to elicit the series’ sense of wonder thanks in no small part to its charming characters, and its stellar soundtrack composed by Hirokazu Tanaka.

For the game’s finale, Mario boarded the SkyPop for a final fireball fueled showdown against Tatanga. The battle was fast and fierce, but eventually the alien was defeated. Mario at last rescued Daisy and boarded a rocketship to the stars.

Super Mario Land had its shortcomings, but it was an extremely memorable experience. The vast majority of its unique elements would rarely, if ever, be revisited, but there was an undeniable magic in the game that made it instrumental to the Game Boy’s initial success with Super Mario Land alone selling over 18 million units. It was yet another hit for Nintendo, and is still widely considered a beloved classic today.

But for as great as Super Mario Land was, it still paled in comparison to what was just over the horizon. So while players across the country waited with baited breath for the impending release of Mario’s third NES adventure, he was about to test his popularity in a new format, syndicated television.

On July 20, 1986, the very first movie projects based on video game properties were released in Japan. One was adapted from Hudson Soft’s Star Soldier, and the other was Super Mario Bros.

The Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach! was an animated theatrical release that saw Mario and an oddly colored Luigi pulled into their television set and transported to the Mushroom Kingdom, where they, as the title suggests, embarked on a great mission to rescue Princess Peach. The movie was strange, but it proved that the world of Super Mario Bros could work in a non-interactive storytelling format.

Mario would continue to be portrayed via traditional animation in Japan over the next few years, between commercial appearances for games and various other products, as well as a trio of animated specials in 1989 called Amada Anime Series: Super Mario Bros., which retold Japanese fairy tales. But none of these projects, even the commercials, ever left Japan. In fact, in the US, Mario had rarely, if ever, appeared in animated form since his brief appearances in the 1983 cartoon series Saturday Supercade. But with his popularity levels higher than ever in the region, it was only a matter of time before that all changed.

Sometime during 1987, animation studio DIC Enterprises began pitching an idea for a Super Mario Bros. centric series to Nintendo. It would be called the Super Mario Bros. Power Hour and feature animated segments based on a number of different popular NES games including The Legend of Zelda, Castlevania, and Metroid. The Power Hour never came to be, but the project continued to evolve until it became something much more Super.

In volume 7 of Nintendo Power, The Super Mario Bros. Super Show was officially unveiled. It promised to be a hybrid live action and animated series that expanded on the lore established in the hit video games. It premiered shortly thereafter on September 4, 1989, and kids across the country finally got to hear the beloved video game mascot speak for the very first time.

As promised, the show brought the Mario brothers to life like never before. In the live action segments, Mario and Luigi, played by professional wrestler Lou Albano and character actor Danny Wells, would have encounters with famous actors, singers, and other personalities at their plumbing shop in Brooklyn. While the animated segments took place in the Mushroom Kingdom, where the brothers were joined by Princess Toadstool and Toad on madcap adventures that usually drew inspiration from various classic movie and television tropes. King Koopa was the main recurring villain, but his henchmen included the likes of Mouser and Tryclide from Super Mario Bros. 2. Wart, however, was nowhere to be found.

The show was filled with music and sound effects from the games, but the plots were far removed from the action players were used to. Regardless, it was a phenomenal success that only further cemented the Mario Bros. in American pop culture, and continued in various incarnations through the end of 1991.

Mario Madness had seemingly reached a fever pitch. But Nintendo was confident that the best was yet to come. Mario’s next adventure continued to be an unbridled success in Japan, and given the series popularity in North America, it was sure to be just as big, if not bigger, when it arrived overseas.

The NES release, though, was still a long way off. So Nintendo made plans to take advantage of this extra time with a unique marketing opportunity.

Before the Super Mario Bros. Super Show had taken over the television airwaves, Universal Studios approached Nintendo with an idea. Instead of creating a film adaptation of one of their properties, they wanted to make something more about gaming itself, drawing inspiration from The Who’s Tommy, a movie about a pinball savant. Nintendo approved, and the timing couldn’t have been better. Mario 3 may have been slated to miss 1989 holiday shopping season, but its first major promotion would now be a major motion picture.

The Wizard was released in movie theaters on December 15, 1989. It told the story of a kid named Jimmy Woods who was struggling to come to terms with the death of his twin sister, and developed a fixation on trying to reach California. After being sent to an institution, his step brother Corey broke him out, and the pair ran away from home, heading for the West Coast. Along the way, they met a girl named Haley who discovered that Jimmy was something of a video game prodigy. So the three children teamed up to enter a video game tournament in Hollywood California called Video Armageddon. It was a surprisingly earnest movie, touching on topics like loss and loneliness through a kids perspective. It was critically panned, and it was obvious that it only really existed to promote Nintendo and Universal Studios theme parks, but it took itself just seriously enough to connect with kids in addition to marketing to them.

Eventually, the trio made it to California where Jimmy faced off against a number of opponents, progressing all the way to the finals where the event’s host informed everyone that they would be competing in a brand new game.

More hijinks ensued involving a bounty hunter, a Power Glove sporting rival named Lucas, and the kids families trying to bring them home, but it all led to this one unforgettable moment.

For many gaming enthusiasts at the time, Super Mario Bros. 3 was already something of a known quantity, between several gaming magazines extensive coverage of its Japanese release, and Nintendo’s own Playchoice10. But for the general public, this movie was the first they had ever heard of it, and it most certainly wouldn’t be the last.

The game’s marketing machine was ready to kick into high gear, as Nintendo unleashed their $25 million ad campaign across the united states. No video game before had ever garnered this much anticipation, and before long, the wait was over. It was finally time to bring Mario’s new adventure home.

Super Mario Bros. 3 was released on the Nintendo Entertainment System on February 12, 1990, and delivered everything it promised and more. Thanks to the inclusion of the new MMC3 chip in the cartridge, Super Mario 3 was a technical powerhouse showcasing visuals, sound, and effects that few games on the platform would ever accomplish. But most importantly of all, the game was positively bursting at the seams with innovation, creativity, and fun.

Mario and Luigi once again found themselves punching question blocks and throwing fireballs just like they did in Super Mario Bros., but every single aspect of the game had been improved upon exponentially. Character control was more precise than ever. The camera could now scroll freely in every direction, including diagonally. Enemies, characters, and backgrounds were bright, colorful, and filled with secrets, and the music was more varied than in any previous entry in the series. The game’s structure was revamped with the introduction of a world map. Where before, level progression was linear, now players could choose which stages they wanted to tackle in whatever order they saw fit, sometimes even allowing the opportunity to skip over some entirely. But it wouldn’t be a new Mario game without new powerups and abilities, and Super Mario Bros. 3 had them to spare.

The Mario bros could now fill a power meter if they were able to run long enough across a flat surface. This would allow them to reach an even faster running speed, something that when mastered would prove to create incredible speedrunning opportunities. But the power meter’s most important function was actually tied to the game’s signature new powerup, the Super Leaf.

Once obtained, Mario or Luigi would sprout a raccoon tail that, as Nintendo Power previously teased, would allow them to fly for a limited time. This was more than just a neat trick, as the level design was built around players having the ability to reach new heights. Hidden areas, secret coins, and more littered the skies, encouraging unprecedented levels of exploration for a Mario game. There was also a Frog Suit that helped with swimming, a Hammer suit that effectively turned Mario into a Hammer Brother, a Magic Whistle based on the Recorder from The Legend of Zelda that opened up Warp Zones, the rare Tanooki Suit that worked the same as the Super Leaf in addition to granting the ability to turn into an invincible statue, and more. These items didn’t all need to be found in stages either. Scattered throughout the various world maps were special icons like Toad Houses, Hammer Brothers, and spade panels where players could earn and store an inventory of powerups that they could enable before entering a stage.

As far as the game’s setting was concerned, it saw the Mario Bros. return not just to the Mushroom Kingdom, but the Mushroom World, a series of eight different countries beyond the borders of the original Super Mario Bros. Bowser was back, but his plans this time weren’t centered around kidnapping the princess. Instead, he had instructed his seven children to steal a series of magic wands and transform the various Kings of the Mushroom World into animals. Princess Toadstool set Mario and Luigi off to retake the wands, and return peace to the world.

The ensuing adventure was massive, taking the plumbers to strange and wondrous new locales like the aquatic Water Land, the labyrinthine Pipe Land, and the eye popping Giant Land, each filled with exciting new challenges meant for players of all skill levels to enjoy. Classic enemies like Lakitu, Goombas, Koopa Troopas and Bob-Ombs were joined by newcomers like Spikes, Chain Chomps, Thwomps, and Boos, most of which would become series staples. There was even a special bonus vs. minigame that would allow players to compete in a modern reimagining of the original Mario Bros. at any time.

At the end of each world, the heroes. would have to face off against one of the Koopa Kids on their flying airship. Once defeated and the magic wands reclaimed, the Kings were returned to their original forms, after which the player would receive a letter from the Princess which contained useful hints, and a special item to help them on their way. But upon completion of World 7 and the final Koopa Kid, the letter awarded wasn’t from Princess Toadstool, but from Bowser himself. It turned out that the Koopa Kids were merely a distraction all along to get the pesky plumbers out of the way for Bowser to once again Kidnap Princess Toadstool. She was being held in his castle in Dark Land, game’s final world which was filled with deadly traps, expert-level stages, and an army of tanks. Upon reaching Bowser’s Castle and overcoming the challenges within, players finally came face to face with the evil sorcerer, and this time battling him would be far more dangerous and complex than simply running past him to grab an ax. Bowser was a fast, intimidating presence who breathed fire and repeatedly tried to flatten Mario with his own surprisingly impressive jumping capabilities.

In the end, the Mario Bros. put a stop to Bowser’s wicked plans and rescued the Princess, who saw fit to tell a particularly disheartening joke for anyone who had previously spent countless hours playing Super Mario Bros. Humor aside, the day was saved, and Mario’s adventure was at an end.

Super Mario Bros. 3 was more than just a success, it was a genuine cultural phenomenon. It was a joyous experience that was exquisitely and lovingly crafted by its creators, so much so that they included a special message at the back of the instruction manual thanking them for giving it a chance, and challenging them to find the staggering number of secrets within. To help, Nintendo released a full-blown strategy guide as the 13th issue of Nintendo Power.

Super Mario Bros. 3 quickly became the best selling video game of all time. It got its own line of Happy Meal toys. The Super Mario bros. Super Show changed to The Adventures of Super Mario Bros. 3. And for the first time outside of Japan, Mario would go on even more adventures in the pages of comic books.

In April 1990, Valiant Comics launched the first entry of what they would call the Nintendo Comics System, with Super Mario Bros. Special Edition #1. The line would eventually grow to include stories based on The Legend of Zelda, Captain N: The Game Master, and more. But no property garnered more attention than Super Mario Bros. Each issue contained a series of short stories based on the worlds of Mario with some strangely inconsistent visual designs. Certain images of the core cast were clearly repurposed from official artwork, while King Koopa was modeled after his appearance in the Super Mario Bros. cartoons, and others like the Mushroom King and the Mushroom Retainers looked unlike nearly anything Nintendo had ever produced before. They had their fans, but none of these series lasted long, with the final issue of the Nintendo Comics System releasing just over a year after its launch.

Also in 1991, Nelsonic Industries released their second Mario Game Watch, Super Mario Bros. 3. But while it featured images and artwork from the NES game, and even included some of its musical score, this wasn’t actually an adaptation of Super Mario Bros. 3 for NES. It was a direct sequel to the 1989 Super Mario Bros. Game Watch.

Two years after saving his sweetheart, the Princess, from the Koopa Dragon, the monster somehow returned and kidnapped her himself, this time seemingly working alone, as the witch mentioned in the first game is never referenced. Mario once again must make his way past numerous creatures, here given strangely off-brand names like poison mushroom and fire-breathing tortoise, collect powerups, and reach the top of the screen to confront, or as the instruction manual grimly states, kill, the Koopa Dragon.

Controls this time around were vastly improved, partly thanks to the much larger buttons on the watch face, and no longer requiring players to simultaneously press two buttons to jump forward. Like its predecessor, it was simple, but effective, and only added to the runaway popularity of Nintendo’s mascot.

Both in Japan and North America, Super Mario Bros. 3 reached unprecedented levels of success and popularity, but the story of how people in various parts of the world experienced the series' evolution to this point was fascinatingly different.

In Japan, players went from Super Mario Bros., to Super Mario Bros. Special, Super Mario bros. 2, then Super Mario Bros. 3. Every followup to Super Mario Bros. before 3 built on the same foundations, taking place in the same world, reusing the same assets, and effectively telling the same story. Making Super Mario Bros. 3 a sudden and monumental evolution for the franchise.

But in North America, Super Mario Bros. led to Super Mario Bros. 2, Super Mario Land, then Super Mario Bros. 3, presenting a much more clear and gradual evolutionary path, contrary to the series' actual development.

To American audiences, Mario 3 wasn't just a huge leap forward, it was the culmination of everything that came before it.

Multi-directional scrolling, using doors to access new areas, Picking up, carrying, and throwing enemies and items, recurring minibosses, multi-tiered environments, auto scrolling stages, these were all brand new features on Famicom, but natural next steps on NES. Even the return of King Koopa was noteworthy. While in Japan, every mainline game had tasked the Mario Bros. with rescuing the Princess from Bowser, in North America, their adventures were far more diverse and resulted in the development of his own rogue’s gallery, first facing Bowser in the Mushroom Kingdom, then Wart in Subcon, and Tatanga in Sarasaland.

But no matter how players got there, or what part of the world they lived in, the general consensus was that Super Mario Bros. 3 was the ultimate 8-bit Mario game. Nintendo had succeeded in delivering yet another generation-defining experience, But success in the video game industry never goes unchallenged for long, and Nintendo was about to face its most fearsome competition yet.

Join us next time as Mario plays with power, super power, and enters the competitive realm of 16-bit gaming in a whole new world.